As a member of the Neighborhood Advisory Council (NAC) for the Wigle development (aka Midtown West).....I can verify the facts in this article. Developers take the penalty rather than hire 51% Detroiters. The Community Benefits Ordinance is a joke....the NAC has no power to enforce changes that we wanted.....the developer just ignored us.....Leslie Malcolmson

Why Detroit’s tool to force developers to invest in community is coming up short

Some residents and members of city council feel the Community Benefits Ordinance isn’t working—and are proposing changes

This story was produced in partnership with the Race and Justice Reporting Initiative at the Detroit Equity Action Lab, a program of the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights. The initiative is funded by the Knight Foundation, Ford Foundation and Community Foundations for Southeast Michigan.

When she was awarded a subcontract for her company to finish drywall at the Henry Ford Detroit Pistons Performance Center, Kimle Nailer was ecstatic about what she thought was the first big break for her company.

With her contract as president of Nail-Rite Construction, Nailer was promised the chance to employ six workers for about six months. She estimated she would make at least $380,000 to work on the Pistons’ new 175,000-square-foot practice center and corporate headquarters in Detroit’s New Center. Her agreement with the Brinkerteam, a major contractor on the project, included a mentor-protege program for minority contractors where she expected to learn how to estimate, bid on, and manage large development projects

But in the end, Nailer was disappointed. When she finally started, she received little mentoring and only about $5,900. She was able to put two union drywall finishers to work for just seven weeks.

“I didn’t get the financial or educational rewards I expected,” says Nailer, who started her company 25 years ago as a residential contractor and recently added commercial projects. “As a minority contractor, I anticipated a greater opportunity to learn the ins and outs of the industry on larger-scale projects, and to obtain more revenue for the company.”

Detroit is booming with large-scale development projects such as the new Piston’s headquarters, Ford’s Michigan Central Station, and the Fiat Chrysler Automobiles assembly plant expansion.

But small-business owners like Nailer, workers, and neighborhood organizers say Detroiters are getting only a small portion of benefits they should from agreements under Detroit’s Community Benefits Ordinance.

They also believe the price to taxpayers is too high for what Detroiters are getting in return. Besides that, the agreements are not legally binding, and no system for accountability for the developers has been established because the law doesn’t require it.

At the same time, many Detroiters are not benefiting much from the economic boom. The city’s unemployment rate is 8.8 percent—a steep drop from the 28 percent peak in 2009. But that’s dramatically higher when compared to the state’s 4.2 percent rate and the nation’s 3.7 percent unemployment rate. As of 2018, Detroit’s median income was still a paltry $26,249.

Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan did issue an executive order that mandates 51 percent of Detroit workers be hired for developments that receive more than $3 million in city funds or tax incentives, but critics say the order has no teeth and developers are not hiring many Detroiters.

Kenneth L. Harris, president and CEO of the National Business League, the nation’s largest black business organization, says black business owners in Detroit have been largely locked out of the large developments underway in the city. Harris, who led the 2017 acquisition of the organization by the Michigan Black Chamber of Commerce, says it’s advocating for black businesses to get a larger share of opportunities the development projects should be bringing.

“We need stronger inclusion policies that are leading to real equity,” he says. “There’s really no excuse for this large of a percentage of black-owned businesses to be excluded, especially with projects that have been subsidized by those businesses and residents. There should be a return on investment and inclusion.”

In September 2018, City Council Pro Tem Mary Sheffield introduced an ordinance to add stiff penalties for developers who don’t hire 51 percent of Detroiters on development and demolition projects and is striving to get the $3 million threshold lowered. But it hasn’t passed City Council yet.

The Community Benefits Ordinance, a law that requires developers to proactively engage with the community to identify community benefits and address concerns about the negative impact of projects, was adopted by voters in November 2016. In the CBO process, a Neighborhood Advisory Council of nine representatives is selected from the project’s impact area to work with developers to mete out community benefits.

The representatives and community benefits are named in the final development agreements, which are approved by the Detroit City Council and meant to ensure that neighborhoods surrounding the developments actually see improvement. Ideally, Detroiters would be hired to work on them and local businesses would get contracts to help build them.

But legal experts and community advocates say the agreements are not favorable enough to the community, and taxpayers are getting little for the millions of dollars that take away from the city.

For the nearly $20 million in brownfield redevelopment tax reimbursements awarded to the $90 million Pistons center, resident benefits include an employment placement program to ensure the facility hires as many Detroiters as possible, and $2.5 million to build 60 outdoor basketball courts in parks across the city.

It also includes $100,000 for workforce training, $600,000 earmarked over six years for youth jobs with the Piston’s organization, 20,000 free tickets each season, and some community access to the facility, including at least one public practice each season.

The direction in which projects are moving forward today is not what Linda Campbell, co-founder of the People’s Platform, a coalition of at least 30 organizations, had in mind when she and others began organizing in the spring of 2013 to craft the nation’s first community benefits ordinance.

“It was becoming obvious that black Detroiters were getting locked out of community development in Detroit, and huge tax incentives were going to billionaires,” says Campbell, who has been a community advocate and organizer for 45 years.

“We weren’t seeing investment in our neighborhoods.”

Gathering representatives from labor, business, and neighborhoods, the groups knocked on doors and met in church basements, before taking their ideas to the Detroit City Council. Some council members supported the idea and formed workgroups. The process was moving along, Campbell says, but then it stalled for three years.

In March of 2016, the People’s Platform decided to take steps to get the ordinance placed on the ballot for the November 2016 election.

“We wanted development projects greater than $15 million and $300,000 in public investments to have to meet with the community to establish a legally binding agreement,” Campbell says. “We wanted so many acres of green space for children, we wanted a level of affordable housing, social and cultural programs for our seniors, a senior lunch program for three or four years, and we wanted education programs and job training.”

The People’s Platform also hoped that the representatives meeting with developers would be largely composed of community members.

But right when the initiative was set to go on the ballot, the Detroit City Council presented its own proposal for a community benefits ordinance. The People’s Platform’s initiative was called Proposal A; the city council’s initiative was called Proposal B. On Election Day, although the people’s initiative passed, Proposal B got more votes and went into effect.

Instead of neighborhood advisory councils of mostly community representatives, they are now composed of nine representatives, the majority of whom are appointed by the City Council and city officials. Only two community members sit on the advisory councils, which quickly meet and decide on each project’s agreements.

Moreover, the agreements are not legally binding, and there’s no process to make sure developers are held accountable for their agreements with the community.

“It’s weak,” Campbell says. “It’s not what we wanted. In exchange for millions of dollars in public investment, it’s rooted in disrespect for Detroiters.”

Campbell and others also are concerned about how the Fiat Chrysler Automotive plant, Detroit’s first new automotive plant in 30 years, is shaping up. The $1.6 billion project’s public incentives total $385 million and could climb as high as $422 million if the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy approves an additional $37.83 in tax increment financing.

Under the brownfield tax incentive program, the Detroit Brownfield Redevelopment Authority will capture nearly $93 million in state, local, and school property taxes for 30 years. Those taxes will go toward repaying the loans to the redevelopment authority, the city of Detroit, and the Michigan Strategic Fund to develop the site.

The incentive package, as well as the costly accumulation of land, was put together because of the promise of jobs for Detroiters. Through the Detroit at Work Job Readiness program, the city helped prequalify about 11,000 people who applied for some of the nearly 5,000 positions at the automaker’s expansion, where Jeep SUVs will be built. In late September, FCA extended its application window to ensure more Detroiters had a chance to apply.

Laid-off workers from an Illinois plant and temporary workers in Detroit will have first dibs at the jobs, but no one knows if or how many Detroiters will be hired. There are also concerns about the effects of increased pollution in the neighborhoods around the factory.

Campbell said the community coalition will not stop fighting for Detroiters’ benefits.

“Where is the fight for the average Detroiters?” she asks. “If elected officials looked out for everyday Detroiters the way they look out for developers, we’d be in great shape. But they don’t. We wish they fought as hard for us as they do for billionaire developers.”

Now, Campbell and dozens of others have taken steps to get the Community Benefits Ordinance amended, which is legally allowed after the ordinance was effective for one year.

In January 2018, the Equitable Detroit Coalition, a coalition of 32 groups and volunteers in the seven city council districts, presented recommendations for amendments to the Community Benefits Ordinance. They include requests to improve inclusivity to allow more community representation in the process and to require projects that receive public investment to participate in the CBO process.

The amendments also stipulate changing the selection process to avoid clear conflicts of interest among advisory members selected by city officials, giving notice to residents living in the entire census track around projects instead of only about two blocks, a monthslong process instead of one that takes a few weeks, and better enforcement measures with legally binding agreements to ensure developers keep their promises.

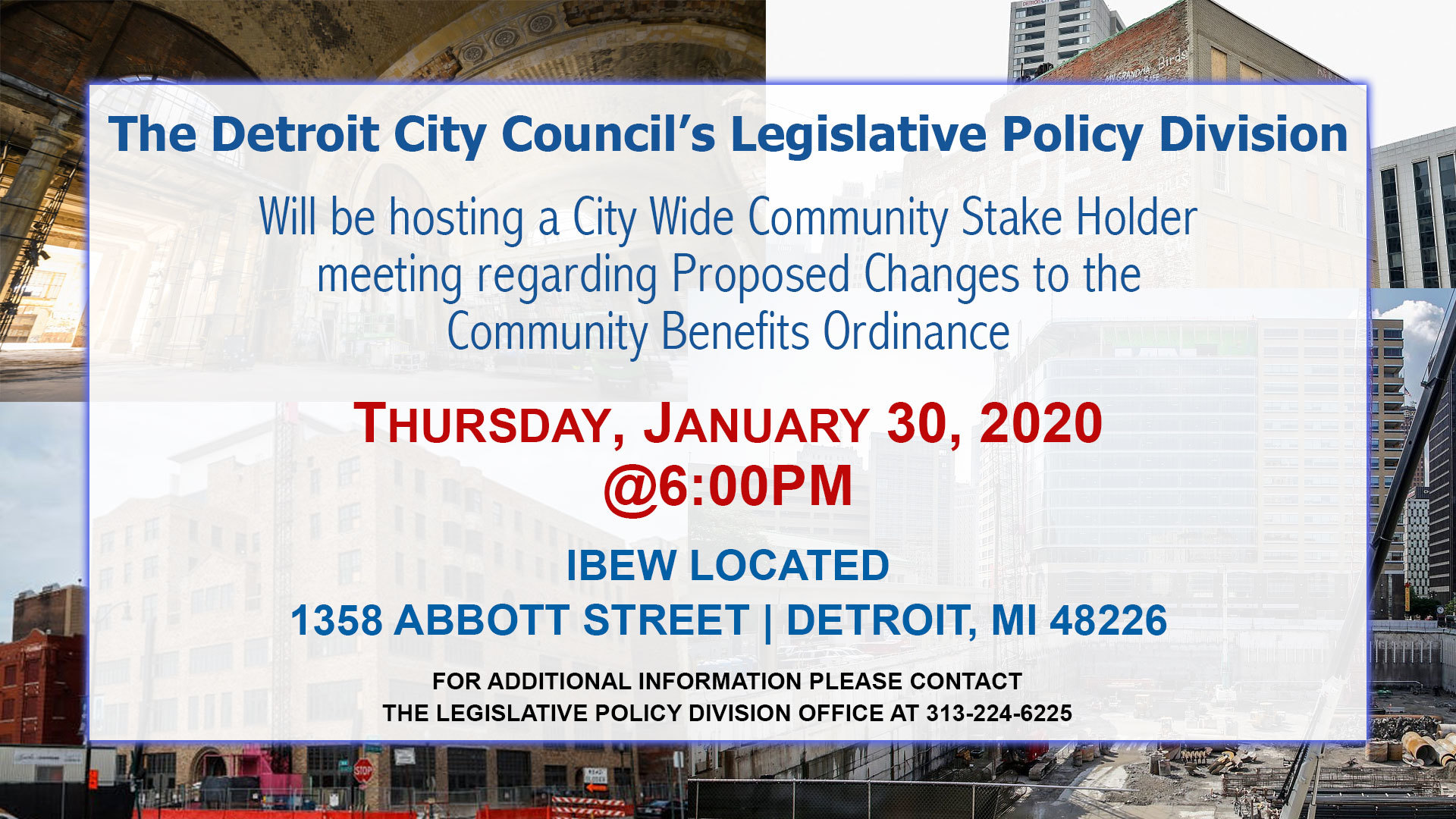

Detroit City Council also seems to think the CBO should be strengthened. The council’s Legislative Policy Division is organizing citywide stakeholder meetings to gather input on potential amendments, and some councilmembers have submitted their own proposals.

One such councilmember is Scott Benson, though he believes the CBO is by and large working as intended. Since its implementation, Benson says it’s added more than $10 billion of investment, a $100 million increase in annual tax revenues to the general fund, more than 12,000 jobs, and other community benefits from outdoor basketball courts, minor home repair grants for low-income residents, and demolition of blighted properties in a project’s impact area, which were negotiated between developers and residents of impacted communities.

He’s proposed only minor amendments to the ordinance.

“I’m concerned any major changes will only discourage future large-scale development in the city, and have a negative impact on the ability to continue the momentum the existing CBO has begun,” Benson wrote in a statement to Curbed Detroit. “Therefore, I submitted amendments that make only minor language changes to the existing ordinance to ensure we are able to continue attracting potential large-scale projects to Detroit.”

He also believes it shouldn’t fall on developers to fix the city. “[The CBO] is not intended to make the new developers responsible for wide-ranging community issues that we, as a city, have failed to or been unable to address,” he wrote.

Councilmember Raquel Castaneda-Lopez believes that while the CBO is sound in theory, it’s in need of modification. “It’s flawed in many ways and doesn’t really support or promote community engagement. It still feels like an afterthought.”

Castaneda-Lopez has submitted a long list of amendment proposals that include neighborhood advisory committees be comprised of community members, a lower financial threshold for the CBO to go into effect, and committee members having direct access to developers without going through the mayor’s office.

“We have to ask ourselves, what’s the cost and what is that the tradeoff?” she says. “Why are we so happy just to take the crumbs? I think that comes from a place of fear and scarcity, which our government very much runs on that mindset locally statewide and federally.

“In the city of Detroit, we deserve more and residents deserve more. We shouldn’t just be taking things because we’re afraid we’re not going to get anything bigger and better.”

https://detroit.curbed.com/

|

Detroiters want more benefits, enforcement from city’s Community Benefits Ordinance - Curbed Detroit

This story was produced in partnership with the Race and Justice Reporting Initiative at the Detroit Equity Action Lab, a program of the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights. The initiative is ...

|